projects

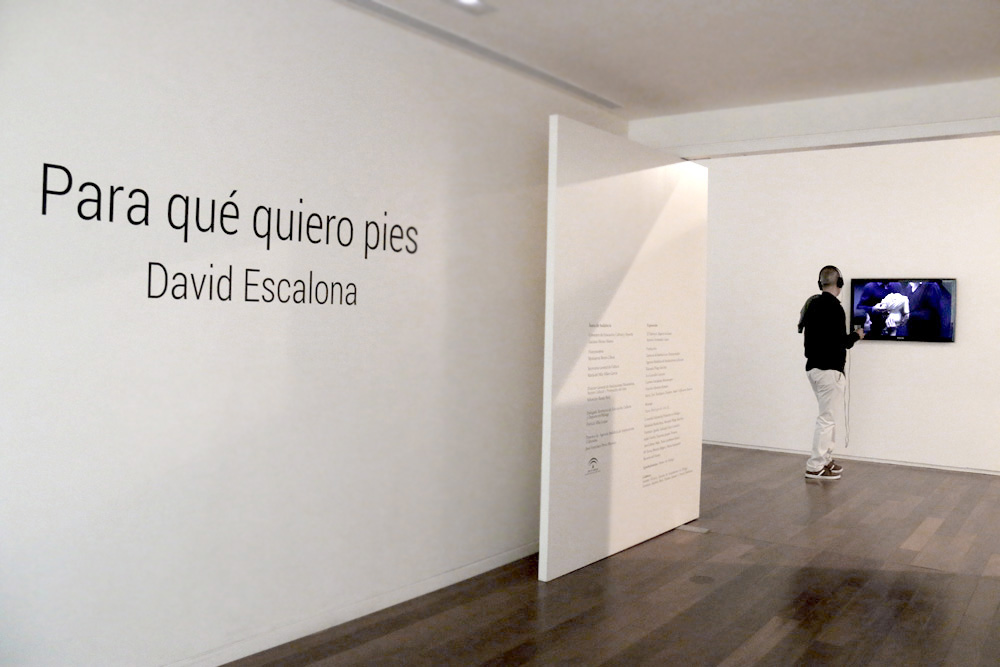

All ProjectsWhat do I want feet for? Para qué quiero pies.

Instalación, técnica mixta y materiales varios ( carro de ruedas bañado en oro, pasamanos de madera con braille dorado, trigo, espejo, zapatos, bastón, trompeta, urracas, video y pieza sonora)

Hymns, wings and blows explained. Alberto Ruiz De Samaniego.

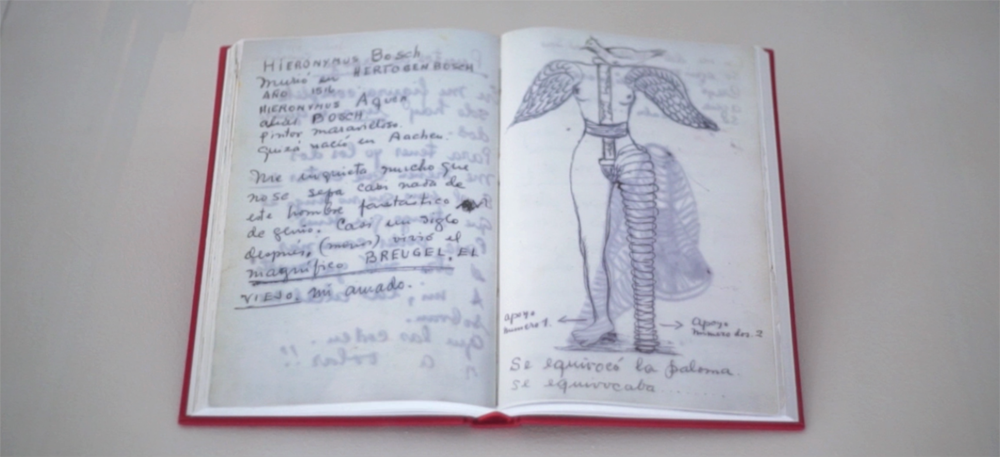

Gods, in mythology, come to us through their winged icons. Like Hermes, for example, a secretive god with dove’s wings, which John Keats refers to in a famous verse in his poem Lamia: ‘the God, dove-footed’. Frida Kahlo may have been inspired by what is a genuinely worrying, even shocking, text for someone who, like the Mexican painter, had lost a leg. She may have been inspired by Keats when producing these drawings and notes for her diary which David Escalona reveals to us here in this exhibit. But perhaps she wasn’t. In any case, the gods, crawling along like human snakes or Lamias or circling above us in the form of doves or other flying animals, always come from elsewhere. They come from afar, thus their contact is often as splendid as it is awful. Like Apollo the Hyperborean, they enjoy appearing suddenly and fleeing into the distance – their distance.

Apollo is a driver and he has a golden carriage. Apollo’s carriage may take us far away, as golden arrows come from afar; arrows which the god – beloved and sometimes terrible – maims us with. Apollo is the charioteer of longevity, or of time.

God of the golden bow,

And of the golden lyre,

And of the golden hair,

And of the golden fire,

Charioteer

Of the patient year ,

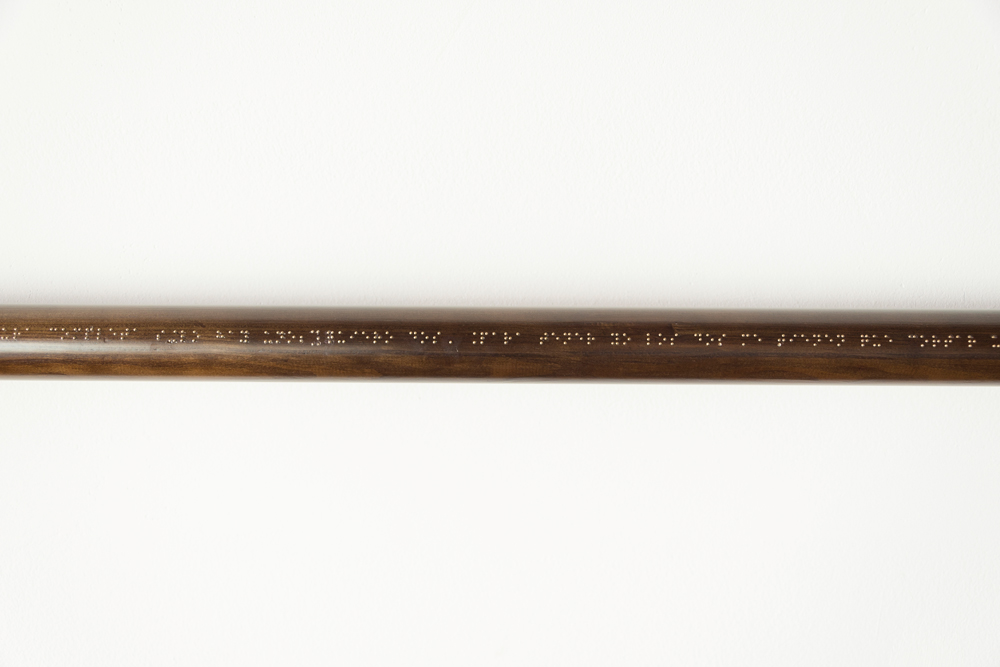

Bathed entirely in gold like this is how Hymn to Apollo begins, also by poor John Keats, he who wrote his name in water, a blow, true, fatal, from god. This should come as no surprise, since gold is an element that characterises this particular deity. Even at his birth, on an arid islet, at that very moment the small strip of land was covered in gold and he received his reward: he settled in the middle of the Greek sea, taking the name of Delos: the Sparkling One. Apollo’s radiance, the gold of light and day completely permeates David Escalona’s exhibit: written in gold on vinyl and in braille, in 24-carat gold which, majestically, plates a wheelchair, – a successful contemporary avatar for Apollo’s carriage. It takes the shape of wheat – the cereal which, together with the vine and the olive, constitutes Mediterranean civilisation’s determining triad, and is an essential component of Eleusinian Mysteries. Mounds of golden wheat, which in this exhibit are waiting, under the open sky, for wind or birds to take them on a journey, undoubtedly to maturation; other transformations, other mouldings and kingdoms. Above them, there are some unused shoes and a black bird that can no longer fly. Under them, there is a cane, staff or snake that was there to help people, perhaps struck by Apollo’s golden arrows, walk on with difficulty. It is, basically, in light form, which is also powerful and radiant. With regard to the Mediterranean Sea, which comes in through the exhibition hall’s large transparent glass screen, to then pause and even linger on the phenomena and appearances of unsuspected reflections before a large ballet mirror installed by the artist.

Everything, then, like a great window opened onto the sea, seems to offer itself to the charges of the sun god’s benevolent and sometimes instant rays day after day; as well as to the hustle and bustle of the port. Everything yields among water fused with light, like in Rimbaud’s Eternity:

Elle est retrouvée

Quoi?– L’Êternité.

C’est la mer allée

Avec le soleil.

Everything is sung and celebrated and reiterates even through the very movement of the pond of frozen water of the great mirror. A mirror placed there to make the air, brilliance and light, dance: the water of the world. It is no surprise, then, that Alberti’s dove mistook “wheat for water”. Just as it is no surprise that

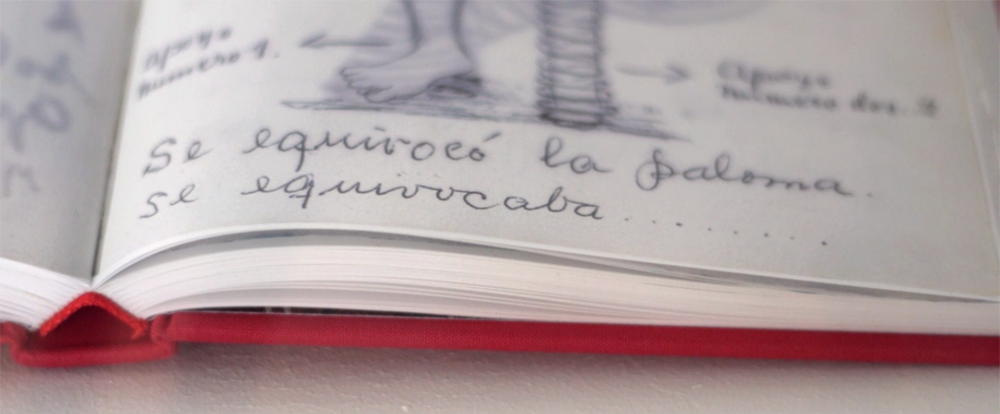

there are drawings of winged beings, sometimes accompanied by the words that give the exhibit its title: (“Feet, what do I want them for if I have wings to fly?”). Not even Frida herself took down Alberti’s famous verse (“The dove was wrong…”) together with her Self-portrait with wings and a dove. The verse was from this poem:

The dove was wrong.

It was mistaken…

By heading north, it went south.

It supposed wheat was water.

But it was mistaken.

It thought the sea was the sky;

and the evening, the morning.

It comes as no surprise because this fusion, such confusion, is the dance of life, the world’s immemorial dance that myths have always sung, through just the voices, hands and bodies of poets, their creators.

The gods, however, are not always to be trusted. It could be said that they are like serene Rilke-esque angles who do not deign to destroy us. Their light, this light and beauty could, effectively, be lethal. Apollo was reportedly the god of poets, fortune tellers and the inspired. The mantic, Delphic, oracular Apollo; his lightning bolts could strike from a distance, and like a dangerous injury, makes mortal men sing. Therefore it has sometimes been said that poets are also light, winged beings. Let us remember what Plato tells us: “Poets are transported and owned like bacchantes (…) they wallow in natural springs and drink in the gardens and wooded hills of Muses like bees, and swarm just like them.” (Ion, 534 a-b). It could be said that they are birds. In fact, like Apollo’s bird, – which was a raven – poets are no more than the gods’ intermediaries. Poets are, to all intents and purposes, as empty spaces. Or, as Keats himself would say: poets “are everything and nothing: they have no set nature; they enjoy both the light and the shade”.

Such availability of empty space is what, among other things, David Escalona wanted to show in the way he used these halls in Espacio Iniciarte in Muelle I. It is an almost entirely deserted open space, so the presence of light, landscape, solar cycles, tides, evening and morning and human routine can descend and settle for an eternal instant, alongside other experiences from Mexico, from Alberti’s poetry, from the sound of the city and the birds, myths, archaeology and history; the closest thing – here wheat is testament to a function the place also had, another refuge: the now-disappeared Málaga Silos used for storing imported wheat to provide for the city in the post-war era and beyond: coming from the mythical depths at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea itself, it speaks of growth and fertility, nutrition and death, regeneration and light, travel and rest and exchange rituals: Eleusis, Apollo-Hermes-Mercury. All this, no less, embraces this exhibit. Because the poet – as good old Keats also wrote – is a chameleon-like being: everyone has substance, as what it needs to do is empty its interior to let the universe in.

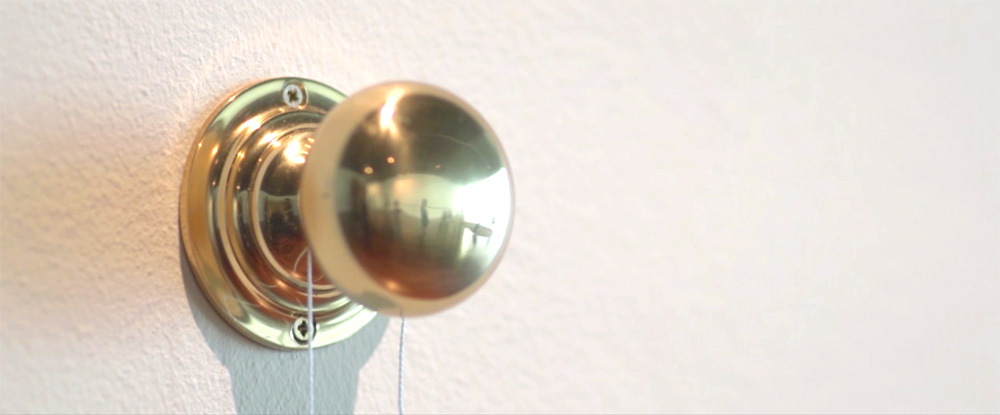

The juxtaposition of codes and materials, of procedures and resources, heterogeneity, the montage of moments, memories and spaces that David Escalona offers us, refer to what the poet has specifically made that no longer speaks of himself – nor from himself – but addresses the same plot of what is real in its intensity of higher or more stunning celebration and plenitude. His task is to transmit-translate it and, sometimes, cut it open from the origins that found it or where it is founded and from where it resonates. To allow, to favour, its golden presence. To give it presence. The paradoxical production’s being is actually this non-being: it is the non-being of the opening through which the instant’s god or radiance dictates, is dictated. Poets are guardians and readers – and even more: a collector of signs, fragments and voices. The person that maintains this opening is preferably someone who listens, embraces and receives as the video emphasises, which David Escalona has prepared since his contact with the statue of Mercury.

This exhibit is all a hymn A song for the sun. Because Apollo is not simply a god who sings, but he is a song himself. A sound-light, if you will. This wonder is what resonates throughout all the elements of the exhibition. All this seems to harmonise in this song, all these different voices (those of Frida Kahlo, Alberti’s dove and the birds in the port, the video and the room, the post-war wheat and the cereal in the Eleusinian Mystery, dance and winged or missing – in the case of the Hermes-Mercury statue – feet, the god of travel and exchanges, blind writing on the ballet bar that shines in the coastal sun, the golden Apollonian carriage, the beings, ultimately, which, although wounded or blind, be them mythological or not, are capable of dancing or flying); they all – we would say – come from one and only Song. From the wonder of a song which everyone remembers without ever mixing it up.

What they are singing, is Apollo. Apollo, who is able to transform into the cosmos, this is: in order and harmony, a confusing and conflicting element ensemble. Apollo, who is able to divide into external relationships and indifferent and jagged appearances. Apollo, who is capable of making classical elements incongruous: earth, sky and sea, a unique, united ensemble, as if it pertained to music. Apollo who, ultimately, purifies and cures. He is the master of purification, in three levels which are on occasion also discreetly or obliquely present in this exhibit: he is Phoebus, the Radiant One, but also the Pure One; the doctor that dispels sickness, the oracle that knows the cause and the remedy. Apollo musicus and medicus. The generous god of the oracle, the god of shape and light. Apollo, who is the light that reveals each and every being. In the words, once again, of Frida Kahlo: “Anything, no matter how horrible, can be beautiful.”

He is not a concrete figure, we understand, he is not a being who could even be named or defined (thus he is athésphatos: beyond words). He is a light or a voice, a light-voice, which fills space; an arrow whose every being is its target. Consequently, Apollo’s carriage, we could say, takes us a long way; just like his bow, it was capable of reaching more distant targets. He is not the god of distance for nothing, which is a concept that, we believe, expresses all the meanings of the exhibit.

Apollo, like Hermes, whose elder brother he is, and Mercury, his Roman incarnation, truly is the god of travel and exchange and of earthly trade, as Casandra states in the Agamenón tragedy of Aeschylus (vv. 1080-1081). Apollo-hinge, between water and light, foreignness or distance and intimacy, between interior and exterior, between city and ocean or sea, between health and sickness, morning and evening, water and wheat, sight and blindness, blind touch and words, phenomenon and reflection, fall and flight, shade and light and life and death themselves. And, in that sense, he is not simply the bright and generous archer, protector of men and crops; he could also be, as we know a fatal and destructive force who, striking so precisely from a distance, destroys; whose word crushes mortals and reveals all their misery. This tension is also present in the exhibit, such ambivalence towards cruelty and redemption, towards rise and fall, as in the very existential case of Frida Kahlo, with a foot cut off, or in the wheelchair itself, or in the statue breaking into pieces, even in the lost dimension, held in Hades, of the wheat germ. In this sense, the ear of wheat was a central element in Eleusinian worship and it is ordinarily used as a symbol of prosperity, or worship to the god Ceres-Demeter, Apollo’s sister in fact, as it was she, according to myth, who invented the method of sowing and harvesting wheat .

All of these beings, ultimately, have been touched by Apollo: angels, we could say, who, when fallen, fight to return, lasting in hell and being beaten by the inspiration that liberates them. A song of liberation and recovery, then, put also a military song, a war song: Apolo Paián. “If Paián is a song about liberty, about recovery (Paeion is the gods’ doctor), it is also a war song. Paio (cf. the latin pavio-pavimento) means strike, damage, hit, beat (which is where clay comes from, pavimentum: man, dancing, flattens the earth).” . Can we not sometimes hear this pattern of tapping sounds, like a sleepless hammer, in the video of Mercury’s damaged, tarnished statue?

The video’s content, its action, never ceases to remind us of one of Rilke’s most beautiful poems, which was inspired when he observed a statue of Apollo’s devastated torso, held in the Louvre, named the Male Torso from Miletus. The poet, finding himself before the battered piece, received a sign ordering him to transform the way he lived his life immediately. Apollo’s power is still there.

ARCHAIC TORSO OF APOLLO

We cannot know his legendary head,

with his eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved beast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark centre where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Walter Benjamin was also affected by Apollo’s torso, certainly through Rilke’s poem, which he admired. In One-Way Street, he explains his thoughts in this aphorism, entitled “Torso” from the Antiques section: “Only those who can view their own past as a product of compulsion and necessity can use it to its full advantage in the present. For what one has lived is at best comparable to a beautiful statue which has lost all its limbs in transit, and now yields nothing but the precious block out of which the image of one’s future must be hewn” . From that point on, there could be no better conclusion or company for David Escalona’s video – or even his whole exhibit.

Damage and repair are not contradictory terms, but the gifts that Apollo’s power compresses or designates. It is about vital power, the impulse that grows and makes plants, humans and animals grow. It is an impulse that can also blind, wound and destroy; it is relentless. Impetus, then, closeness, possession, terror, shouts; in Homeric Hymns Apollonian light is described in terms that recall its complexity and ambivalence.

Keats also notes it in his hymn:

O why didst thou pity, and beg for a worm?

Why touch thy soft lute

Till the thunder was mute,

Why was I not crush’d… such a pitiful germ?

O Delphic Apollo!

The Pleiades were up,

Watching the silent air;

The seeds and roots in Earth

Were swelling for summer fare;

The Ocean, its neighbour,

Was at his old labour,

When, who…who did dare

To tie for a moment, thy plant round his brow,

And grin and look proudly,

And blaspheme so loudly,

And live for that honour, to stoop to thee now?

O Delphic Apollo!

In the same way, David Escalona – even in the very title of the exhibition – salutes the bright, radiant nature of the myth, Apollo phoibos (the Bright one) at the expense of his more nocturnal and terrible aspects which, nevertheless, remain underlying. We would also add that Apollo was known and sung about as a founder and builder of cities, precisely because of his ability to provide the immaterial foundations of a harmonious constitution. Perhaps it is in this same dimension that he is eternally young, the divine kouros (teenage boy), model and protector of human kouroi. The myth, however, continually notes his close relationship with the condemned. Apollo is a killer of saurians, of animals that crawl, he who lives alongside the chthonic beings, the gêgeneis (earthborn). It is a relationship in which complying with the earth, or depending on or submitting to the earth, continually points to the dark side, wounded or fallen, of the bright and celestial being.

Apollo is the archer and lyrist. If the bow resembles the lyre, the poet’s song he inspired also resembles the arrow that, propelled from afar, strikes its target. The poetic word acts, then, like the oracle: it points to truth and arrives at it. But poetry also arrives at a truth that represents, through the music and rhythm that accompanies it, oblivion and relief – the cure or recovery – of what is damaged, or what is separate, the redemption of what is ruined, the regeneration toward the light of the condemned to Hades and night. And the only way to achieve this is by overcoming, which is called harmony; it is an invitation to dance. Consequently Apollo, the archer, is also the zitherist that makes the gods dance. Apollo’s lyre softens and mollifies anything wild, full of disorder or wounded: “Straight away the undying gods think only of the lyre and song… Meanwhile the rich-tressed Graces and cheerful Seasons dance with Harmonia and Hebe and Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus, holding each other by the wrist” Homeric Hymn to Apollo, 188-203). We now know why Apollo is the founder of cities: he is the guarantor, through the medium of harmony, of a well legislated ensemble, of the cities founded on congruous legislation.

It will then be his younger brother, Hermes who certainly made Apollo’s lyre and is always on the move, always under the auspices of anything that belongs to the order of something being introduced: goods, words, roles and bodies. Hermes Works in the extremes, limits and borders between the worlds. He undoubtedly has to be the master of the ports, or preliminary spaces like this Espacio Iniciarte in Muelle I (architectural presence is crucial for this project). Hermes works in exactly the same way as David Escalona has here: joining what had been separated, helping communication in all its forms, from all its journeys and possibilities, however incredibly diverse they were. In his way of acting, alive, fast and fleeting, the wing-footed Hermes takes on a mobility that is, ultimately, that of the world itself. His Roman incarnation, as we know, is Mercury, whose name is bound to be associated with the word merx, meaning merchandise, like wheat, for example. Also, however, in the words of the great poet, Virgil, this is one of the psychopomp’s responsibilities, which is: to escort souls from the world of the living to that of the dead and, at the same time, to tie together their golden wings to their heels to transmit the messages of the divine to mortals and immortals, among the divine: Jupiter. As David Escalona suggests, Mercury quite possibly said to himself at that moment what Frida Kahlo wrote in her Diary: Feet, what do I want them for if I have wings to fly?

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

University of Vigo

Himnos, alas, golpes: esclarecidos.

Alberto Ruiz De Samaniego.

Los dioses, en el mito, llegan a nosotros a través de sus imágenes aladas. Como Hermes, por ejemplo, dios sigiloso que camina con alas de paloma, tal como, en un conocido verso de su poema Lamia lo denominara John Keats: the God, dove-footed, el dios, pies de paloma. Puede que Frida Kahlo se inspirase en este texto, verdaderamente inquietante, y hasta sobrecogedor para alguien que, como la pintora mexicana, había perdido una pierna. Puede que se inspirase en Keats al realizar esos dibujos y anotaciones para su diario que David Escalona nos revela ahora en esta exposición. Puede que no. En todo caso, los dioses, arrastrándose como serpientes humanas o como lamias o circulando por los aires en forma de paloma o de otro animal volador, vienen siempre de otra parte. Vienen de lejos, y por eso su contacto a menudo es tan hermoso como terrible. Gustan, como Apolo el Hiperbóreo, de aparecer súbitamente y huir en la distancia, en su distancia.

Es un conductor, Apolo, y su carro es de oro. El carro de Apolo acaso nos lleve lejos, como de lejos vienen las flechas de oro con que el dios – amado y por veces terrible – nos lacera. Apolo es el auriga de la duración, o del tiempo.

God of the golden bow,

And of the golden lyre,

And of the golden hair,

And of the golden fire,

Charioteer

Of the patient year ,

Así, bañado en oro al completo, comienza el Himno a Apolo, también del pobre John Keats, el que escribió su nombre sobre el agua; un golpeado, verdaderamente, fatalmente, por el dios. No ha de extrañarnos, pues el oro es un elemento que caracterizará a esta divinidad. Ya en su nacimiento, en un árido islote, al punto esa pequeña franja de tierra se cubre de oro y recibe su recompensa: arraiga en el centro del mar griego tomando el nombre de Delos: la Brillante. El resplandor de Apolo, el oro de la luz y de los días, penetra enteramente la exposición de David Escalona: en forma de escritura dorada en vinilo y en braille, en forma del oro de 24 kilates que, majestuoso, baña una silla de ruedas – he ahí un logrado avatar contemporáneo del carro de Apolo-. Penetra en forma de trigo – el cereal que, junto con la vid y el olivo, constituye la tríada determinante de la civilización mediterránea, y es un componente esencial de los misterios eleusinos-. Montículos de trigo áureo que en esta exposición esperan, a la intemperie, la participación del viento o de los pájaros para un nuevo viaje sin duda iniciático; otras transformaciones, otras molduras y reinos. Sobre ellos, unos zapatos inutilizados, y un pájaro negro que ya no volará. Bajo ellos, un bastón, báculo o serpiente que sirvió a alguien para caminar penosamente, tal vez otro golpeado por las flechas de oro de Apolo. Penetra, en fin, en forma de luz, ella también poderosa, esplendorosa. La del mar Mediterráneo que entra por la gran pantalla de vidrio transparente de la sala de exposiciones, para luego detenerse y hasta persistir en los fenómenos y apariencias de insospechados reflejos que premedita un gran espejo de ballet instalado por el artista.

Todo allí, pues, como gran ventana abierta al mar, parece ofrecerse día tras día a las acometidas de rayos benéficos y por veces fulminantes del dios solar; a los trajines también del ajetreo portuario. Todo se da entre el agua y la luz fundidas, como en la eternidad de Rimbaud:

Elle est retrouvée

Quoi?– L’Êternité.

C’est la mer allée

Avec le soleil.

Todo se canta y se celebra y reitera incluso a través de los propios juegos en el estanque de agua congelada del gran espejo. Un espejo puesto allí para que baile el aire, el fulgor, la luz: el agua del mundo. No es extraño que la paloma de Alberti se equivocase, y creyese entonces “que el trigo era agua”. Como no es extraño que en los diarios de Frida Kahlo aparezcan dibujos de seres alados acompañados en alguna ocasión de las palabras que dan título a esta exposición: (“Pies para qué los quiero si tengo alas pa´ volar”). Ni que la misma Frida copiase junto a su Autorretrato con alas y paloma el verso conocido de Alberti (“Se equivocó la paloma…”), perteneciente a este poema:

Se equivocó la paloma.

Se equivocaba…

Por ir al norte, fue al Sur.

Creyó que el trigo era agua.

Se equivocaba.

Creyó que el mar era el cielo;

que la noche, la mañana.

No es extraño, porque esa fusión, tal confusión, es la danza de la vida; la danza inmemorial del mundo que los mitos siempre han cantado, a través precisamente de la voz, la mano y el cuerpo de los poetas, de los creadores.

Aunque los dioses no son del todo de fiar. Se diría que ellos son como los ángeles rilkeanos, que, serenos, desdeñan destruirnos. Su luz, esa luz y belleza puede, efectivamente, ser letal. Es fama que Apolo es dios de poetas, adivinadores e inspirados: Apolo mántico, délfico, oracular: su rayo toca desde la distancia y, como una peligrosa herida, provoca el canto en el hombre mortal. Tal vez por eso se ha dicho que los poetas son también cosa ligera, alada. Recordemos lo que nos cuenta Platón: “Los poetas son transportados y poseídos como las bacantes (…) se abrevan en manantiales y hacen libaciones en los jardines y las boscosas colinas de las Musas, a la manera de las abejas, y revolotean como ellas.” (Ion, 534 a-b). Se diría que son pájaros. De hecho, como el pájaro de Apolo – que era un cuervo – el poeta no es más que un cuerpo intermediario del dios. En su total disponibilidad, él es en realidad como un vacío. O, como diría el propio Keats: el poeta “lo es todo y no es nada: no tiene carácter; disfruta de la luz y de la sombra”.

Tal disponibilidad del vacío es lo que, entre otras cosas, ha querido evidenciar David Escalona en el uso de estas salas del Espacio Iniciarte del Muelle I. Un espacio abierto, casi desierto, para que las presencias de la luz, el paisaje, los ciclos solares, loa flujos marítimos, la noche y la mañana y el tráfago humano puedan finalmente descender, y allí asentarse por un instante eterno, en convivencia con otras experiencias que vienen de México, de la poesía de Alberti, del sonido ciudadano y el de los pájaros, del mito, de la arqueología y de la historia; la más próxima – aquí el trigo sirve como testimonio de una función que este lugar también tuvo, otra acogida: el desaparecido Silos de Málaga, destinado al almacenamiento del trigo importado para abastecer a la ciudad en los años de posguerra- y la más lejana: la que viene del hondón mítico que funda el propio mar Mediterráneo, y que habla de ritos de crecimiento y fertilidad, de nutrición y muerte, de regeneración y luz, de viajes y descensos y de intercambio: Eleusis, Apolo-Hermes-Mercurio. Todo esto, nada menos, acoge esta exposición. Porque el poeta – escribió también el bueno de Keats- es un ser camaleónico: todos los seres tienen un contenido, mientras él lo que tiene que hacer es un vaciado de su interior para dejar entrar dentro de él al universo.

La yuxtaposición de códigos y materiales, de procedimientos y recursos, la heterogeneidad, el montaje de tiempos, memorias y espacios que David Escalona nos ofrece, remiten a este específico hacer del poeta que ya no habla de sí – ni desde sí- sino que hace hablar a la trama misma de lo real en su intensidad de celebración y plenitud más altas o fulgurantes. Su tarea consiste en transmitirla-traducirla y, acaso, hendirla desde lo originario que la funda o en donde está fundada y desde donde resuena. Permitir, favorecer su presencia áurea. Darla a presencia. El ser de su paradójica producción es propiamente ese no-ser: es el no-ser de la abertura a través de la cual el dios o el fulgor del instante dicta, se dicta. El poeta es un guardián y un lector – y aún más: un recolector- de signos, de fragmentos y de voces. El mantenedor de esa abertura, alguien que preferentemente escucha, acoge y recibe, como enfatiza el vídeo que David Escalona ha preparado a partir de su contacto con la estatua de Mercurio.

Esta exposición es toda ella un himno, un himno a Apolo. Un canto solar. Porque Apolo no sólo es un dios que canta, sino que él mismo es un canto. Si queremos, un sonido-luz. Este prodigio es lo que resuena a lo largo de todos los elementos de la muestra. Todos ellos parecen armonizarse en ese canto, todas esas voces distintas (la de Frida Kahlo, la de la paloma de Alberti y los pájaros del puerto, del vídeo y de la sala, la del trigo de posguerra y el cereal del mito eleusino, la del baile y los pies alados o desaparecidos de la estatua de Hermes-Mercurio, el dios de los caminos y los intercambios, la de la escritura ciega sobre la barra de baile que brilla con el sol de la marina, la del carro de oro apolíneo, la de los seres, en definitiva, que, aun heridos o ciegos, sean mitológicos o no, son capaces de bailar o volar) todos – decíamos- derivan de un solo y único Canto. Del prodigio de un canto que todos evocan sin confundirse nunca entre sí.

Lo que cantan es Apolo. Apolo que es capaz de convertir en cosmos, esto es: en orden y armonía, un conjunto confuso y discordante de elementos. Apolo que es capaz de resolver en relaciones eternas apariencias indistintas y melladas. Apolo que es capaz de hacer de los elementos fundacionales discordantes: tierra, cielo y mar, un único conjunto cohesionado, como si de una música se tratase. Apolo que, en definitiva, purifica y cura. Señor de las purificaciones, lo es en tres niveles, que acaso están presentes de forma también sigilosa u oblicua en esta exposición: él es Febo, el Resplandeciente, pero también el Puro; es el médico que aleja el mal; es el oráculo que conoce la causa y el remedio. Apolo musicus y medicus. El dios bienhechor del oráculo, el dios de la forma y de la luz. Apolo que es la luz que revela cada ser. En palabras otra vez de Frida Kahlo: “Todo puede tener belleza, aún lo más horrible.”

No es una figura concreta, entiéndasenos, no es un ser siquiera que pueda ser nombrado o definido (por eso es athésphatos: indecible). Es una luz o una voz, una luz-voz, que llena el espacio; una flecha de la cual cada ser es el blanco. Por eso el carro de Apolo, decíamos, nos conduce lejos, tanto como su arco era capaz de alcanzar los blancos más alejados. No por nada él es el dios de la distancia, un concepto que, creemos, articula todos los sentidos de esta exposición.

Apolo, como Hermes, de quien es su hermano mayor, o Mercurio, su versión latina, es verdaderamente el dios de los caminos y de los intercambios, de los comercios sobre tierra, tal como Casandra declara en la tragedia Agamenón de Esquilo (vv. 1080-1081). Apolo-gozne, entre agua y luz, extranjería o lejanía e intimidad, entre interior y exterior, entre ciudad y océano o mar, entre salud y enfermedad, mañana y noche, agua y trigo, visión y ceguera, tacto ciego y palabra, fenómeno y reflejo, caída y vuelo, sombra y luz, vida y muerte mismas. Y, en ese sentido, no sólo es el arquero luminoso y benefactor, protector de los hombres y de los cultivos, también puede ser, lo sabemos, una fuerza destructora y fatal, el que golpeando precisamente de lejos destruye; cuya palabra aplasta a los mortales y revela toda su miseria. Esta tensión también está presente en la exposición, tal ambivalencia de crueldad y redención, de ascenso y caída, como en el propio caso existencial de Frida Kahlo, con la pierna cortada, o en la misma silla de ruedas, o en la fragmentación ruinosa de la estatua romana; incluso en la dimensión abismada, secuestrada en el Hades, de la semilla de trigo. En este sentido, la espiga era un elemento central en los cultos eleusinos, y es ordinariamente usada como símbolo de abundancia, o de culto a la diosa Ceres-Démeter, la hermana por cierto de Apolo, por ser ella, según la mitología, la inventora del modo de sembrar y recoger el trigo .

Todos ellos, en fin, son seres tocados por Apolo: ángeles, diríamos, que caídos luchan por su restitución, resisten en el infierno y se baten por la iluminación que los libere. Canto pues de liberación y cura pero también canto marcial, canto de guerra: Apolo Paián. “Si Paián es un canto de liberación, de cura (Paeion es el médico de los dioses), es igualmente un canto de guerra. Paio (cf. el latín pavio-pavimento) significa percutir, lastimar, pegar, batir (de ahí la tierra batida, el pavimentum: el hombre, bailando, aplasta la tierra)” . ¿No escuchamos acaso esta seriación de sonidos percutidos, como un martilleo insomne, en el vídeo de la estatua lastimada, mancillada, de Mercurio?

El contenido, las acciones de este vídeo, no dejan de recordarnos uno de los poemas más hermosos de Rilke, aquél precisamente inspirado en la contemplación del torso devastado de una estatua de Apolo que guarda el Louvre, el llamado Torso juvenil de Mileto. El poeta, ante la maltrecha pieza, recibe una señal que le conmina a transformar urgentemente su forma de vida. Es la fuerza de Apolo, todavía:

TORSO DE APOLO ARCAICO

No conocemos la inaudita cabeza,

en que maduraron los ojos. Pero

su torso arde aún como candelabro

en el que la vista, tan sólo reducida,

persiste y brilla. De lo contrario, no te

deslumbraría la saliente de su pecho,

ni por la suave curva de las caderas viajaría

una sonrisa hacia aquel punto donde colgara el sexo.

Si no siguiera en pie esta piedra desfigurada y rota

bajo el arco transparente de los hombros

ni brillara como piel de fiera;

ni centellara por cada uno de sus lados

como una estrella: porque aquí no hay un solo

lugar que no te vea. Has de cambiar tu vida.

También Walter Benjamin se sintió tocado por el torso de Apolo, con seguridad a través del poema de Rilke, que admiraba. En Dirección única, elabora esta reflexión en el aforismo titulado “Torso”, de la sección Antigüedades: “Únicamente quien supiera contemplar su propio pasado como un producto de la coacción y la necesidad, sería capaz de sacarle para sí el mayor provecho en cualquier situación presente. Pues lo que uno ha vivido es, en el mejor de los casos, comparable a una bella estatua que hubiera perdido todos sus miembros al ser transportada y ya sólo ofreciera ahora el valioso bloque en el que uno mismo habrá de cincelar la imagen de su propio futuro” . No puede haber, desde luego, mejor conclusión o compañía para el vídeo de Andrés Escalona – incluso para toda su exposición-.

Lastimar y curar no son términos contradictorios, sino los dones que la fuerza de Apolo condensa o designa. Se trata de la fuerza vital, el impulso que crece y hace crecer a las plantas, los hombres y los animales. Un impulso que también puede cegar, herir, ser destructor: implacable. Ímpetu, pues, inmediatez, posesión, terror, gritos; ya en el Himno homérico la luz apolínea es descrita en unos términos que evocan su complejidad y ambivalencia.

También Keats apunta a esto mismo, en su himno:

O why didst thou pity, and beg for a worm?

Why touch thy soft lute

Till the thunder was mute,

Why was I not crush’d…such a pitiful germ?

O Delphic Apollo!

The Pleiades were up,

Watching the silent air;

The seeds and roots in Earth

Were swelling for summer fare;

The Ocean, its neighbour,

Was at his old labour,

When, who…who did dare

To tie for a moment, thy plant round his brow,

And grin and look proudly,

And blaspheme so loudly,

And live for that honour, to stoop to thee now?

O Delphic Apollo!

En idéntica medida, David Escalona privilegia – ya en el propio título de la muestra- el carácter luminoso y resplandeciente del mito, Apolo phoibos (el Luminoso) en detrimento de sus aspectos más nocturnos y terribles que, no obstante, no dejan de estar latentes. Añadamos, además, que Apolo fue conocido y cantado como fundador y constructor de ciudades, precisamente por su capacidad para proporcionar las bases inmateriales de una constitución armoniosa. Tal vez sea en esta misma dimensión que él es el eternamente joven, el kouros (muchacho) divino, modelo y protector de los kouroi humanos. El mito, sin embargo, no deja de marcar su estrecha relación con lo condenado: Apolo matador de saurios, de los animales que se arrastran, el que convive con los seres ctónicos, los gêgeneis (nacidos de la tierra). En una relación donde la complicidad con la tierra o la dependencia o supeditación a la tierra no deja de insistir en la parte oscura, herida o caída del ser luminoso y celeste.

Apolo es el tañedor del arco y de la lira. Si el arco se parece a la lira, también el canto del poeta inspirado por él se parece a la flecha que, arrojada desde lejos, alcanza su objetivo. La palabra poética actúa, pues, como el oráculo: apunta hacia la verdad y la alcanza. Sólo que la poesía alcanza además una verdad que representa, mediante la música y el ritmo que la acompaña, el olvido o el alivio – la cura o la restauración- de lo lastimado, o de lo disjunto, la redención de lo arruinado, la regeneración hacia la luz de lo condenado al Hades y la noche. Y ello no se logra de otra manera más que a través de esa forma de superación que se llama armonía, invitación a la danza. Por eso el arquero Apolo es también el citarista que hace bailar a los dioses. La lira de Apolo endulza y apacigua todo aquello que es salvaje, lleno de desorden o de heridas: “Bien pronto a los Inmortales les atraen la cítara y el canto…Por su parte, las Gracias de hermosos bucles y las benévolas Horas, así como Harmonía, Hebe y la hija de Zeus, Afrodita, danzan, tomándose unas a otras las manos por la muñeca” (Himno homérico a Apolo, 188-203). Ahora sabemos por qué Apolo es fundador de ciudades: él es el garante, por medio de la armonía, de un conjunto bien legislado, de las ciudades fundadas sobre legislaciones armónicas.

Luego será su hermano menor, Hermes, el hacedor por cierto de la lira de Apolo, quien, siempre en movimiento, patrocinará todo aquello que pertenece al orden de una puesta en circulación: bienes, palabras, roles, cuerpos. Hermes trabaja en los extremos, límites y fronteras entre los mundos. Ha de ser sin duda el señor de los puertos, o de los espacios liminares como este Espacio Iniciarte del Muelle I (la presencia arquitectónica es crucial para este proyecto). Hermes trabaja exactamente de la forma en que aquí lo ha hecho David Escalona: conjuntando lo que está separado, ayudando a la comunicación en todas sus formas, desde todos sus caminos y posibilidades por muy diversos que fuesen. En su modo de actuación, vivo, rápido y fugaz, Hermes, de pies alados, toma a su cargo una movilidad que es, en definitiva, la del mundo mismo. Su versión latina, como sabemos, es Mercurio, cuyo nombre no puede disociarse de la palabra merx, que designa la mercancía, como el trigo, por ejemplo. Pero también, en palabras de un gran poeta, Virgilio, está entre sus funciones la de psicopompo, esto es: conducir las almas del mundo de los vivos al mundo de los muertos y, a la vez, la de atarse sus alas de oro en los talones para transmitir a los mortales e inmortales los mensajes del divino entre los divinos: Júpiter. Como sugiere David, muy posiblemente en esos momentos Mercurio se dijese a sí mismo lo que Frida Kahlo escribió en su Diario: Pies para que los quiero, si tengo alas para volar.

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

Universidad de Vigo